While excellent newsletters on specific themes within public policy already exist, this thought letter is about frameworks, mental models, and key ideas that will hopefully help you think about any public policy problem in imaginative ways. If this post was forwarded to you and you liked it, consider subscribing. It’s free. #266 Complex Questions and Easy AnswersKamandal versus Mandal yet again, and Industrial Policy Promises versus RealityIndia Policy Watch #1: Jaat Na Poochho Sadhu Ki*Insights on current policy issues in India— RSJThe great Indian political sequel looks ready for release. The blockbuster hit of the 90s, Kamandal versus Mandal (K vs M), is back in a new, CGI-enhanced version with a slightly updated storyline and a new cast of characters. And it is giving the other big summer sequel, Deadpool & Wolverine, a good run for its money. I had sensed this political sequel, ‘K vs M - Amrit Kaal’, might be ready for release around 2027. But looking at the trailers shown in the parliament and outside of it this week, I think we will have it in our political theatres by next month, and it looks set for a five-year run. A couple of specific events this week brought back the 90s. Early on in the week, the leader of the opposition spoke on the Union Budget in Lok Sabha, where he raised the economic issues of joblessness, crony capitalism and farmer distress using a chakravyuh metaphor. All par for the course. But then he built on this foundation to attack the government of being of the forward castes, by the forward castes and for the forward castes. To use his metaphor, the same privileged minority accounting for 3-5 per cent of India make the budget ka halwa and then corners all of it for themselves, leaving nothing for the majority backward, Dalit and tribal communities. He rounded off his speech by demanding the caste-based census, which, according to him, will give the legislature and the executive a clear picture of the demographics of various castes and communities and the skew that may exist on their relative economic and social progress. This skew or inequality requires redressal and the government is reluctant to go down this path because it is captured by the vested interests—that was the opposition charge for much of this week. And then on Thursday, in what can only be a coincidence, a seven-judge bench of the Supreme Court delivered a 6:1 verdict permitting sub-classification for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes in reservations by state governments. This will allow state governments to reserve seats for specific sub-groups within the quotas that are aimed at SC and ST communities based on the relative deprivation of those sub-groups. As CJI Chandrachud observed, the judgment places emphasis on substantive equality over formal equality and recognises that there are multiple marginalised sub-groups within the SC and ST monolith who need the specific benefits of affirmative actions. In the absence of such an arrangement, there’s a ‘creamy layer’ within this monolith that is cornering most of the benefits. Reservations, quotas, caste census, Ambedkar, Lohia, Mandal - they are all back in the mix of political issues at the moment. Is this a real shift in political discourse or a passing summer shower? Also, if this is real, as I suspect, what would be its political and economic implications? At various times I have written on these pages the very familiar and now well understood truth about Indian politics. For about four decades now, the fundamental political contest in India has been between forces of consolidation of the Hindu identity largely on the Hindutva plank and the forces that battle this coalescing of sub-identities by highlighting the uniqueness of their aspirations and the fear of being subjugated all over again under a monolith Hindutva project. The genius of BJP and PM Modi in the last decade or so has been their ability to keep the cohering forces of identity consolidation stronger than the natural, centrifugal force of identity division. The relative decline in salience of caste or regional identity among the urban populace and a well-chosen set of welfare initiatives aimed at the poor allowed the BJP to build a much wider Hindu coalition, which worked like a charm in the 2019 elections and held its own since then in various state elections. Till 2024 happened, and it hit what seems like the limit of the consolidation strategy. So, the question is, has the BJP maxed out on this? To answer this, let’s understand the factors that helped it in the unprecedented consolidation of Hindu identity for electoral gains and how strong they are in today’s context. The first factor was the way PM Modi came to represent the most potent challenge to the entrenched power structure of Indian politics. Everything from dynasty politics, secularism, minority appeasement, corruption, lack of accountability, poor execution - all the reasons that ordinary citizens believed held India back were the target of PM Modi’s attack. He had no past baggage of these, and he positioned himself above this through rhetoric, unrelenting Nehru-Congress bashing and by building an image of a hardworking fakir to whom only national interest matters. This positioning allowed him to consolidate the middle class, educated, and young voters who believed the only thing that was stopping India was this deeply embedded power structure. This still remains a strong, perhaps the strongest, of the factors. But ten years of being in power, especially the very personalised way that he has governed has blunted his outsider, challenger persona. You can still speak of 60 years of Congress misrule and rally your supporters but there’s a new generation that has grown up seeing you as the representation of power structure. Further, you have to defend your own track record of a decade that has missteps, which gives the opposition reasons to show you as part of the problem rather than the solution. And this will continue to weaken every additional day you are in power. The only way to control the slide is to ratchet up the ‘60 years of Congress misrule’ rhetoric, more virulent Nehru bashing through fake stories on social media channels and building a more credible narrative of an ecosystem of anti-nationals and global enemies of India who don’t want an outsider like PM Modi to do well. I expect a significant emphasis on these in the coming days. Expect more ED raids on opposition on corruption charges, targeted legal attacks on non-mainstream media stars who speak against the government and more emphasis on the fakiri image of the PM. That apart, the other factor that helped in majority consolidation in the past decade was the new and innovative ways to blame the “other” for everything plaguing the nation. Usually, this “other” was the Muslim minority, but there have been leftists, urban naxals, students, Bollywood, liberals, farmers, Sikhs and anyone else who opposed the government. Nationalism was redefined in a manner that anyone opposed to the government could be shown to be anti-national. This was coupled with the idea of a cultural and national renaissance that was personally led by the PM through symbols like the inauguration of the temple at Ayodhya, repeal of Article 370, love jihad laws in many states and a host of other measures that added up to the notion that under this government, ‘Hindu jaag gaya hai’ (Hindus have awoken). This plank was possibly at its strongest in the run-up to the 2019 elections. Much to BJP’s dismay, this was weak during the 2024 elections. The problem is that of diminishing returns. Until the temple at Ayodhya wasn’t built, you could milk the issue. Once it is built, you cannot live off that credit forever. People move on to other things. Similarly, you can rile up the people with ‘Hindu jaag gaya hai’ once to get things done. Build a temple, muffle comedians who joke about Hindu religious figures, change the history textbooks or whatever else catches your fancy. But once the majority is awake, how do you send it back to sleep for it to be roused again? The problem of getting a large part of your majoritarian consolidation agenda done is what do you do after that? Find newer items on the agenda? But it is not easy to create the emotional heft that the older items have built over the years. Nor will your alliance partners, who you depend on, allow you to go overboard here with new issues. It is likely that the BJP will flail around to find new items to further consolidation and run the risk of overdoing things, as we saw with the nameplate issue in UP during the Kanwar Yatra. Lastly, there’s the question of the economic benefits that the sub-identities who have been consolidated get for participating in the project. After all, a temple or a legislation isn’t going to make their daily lives or the future of their children better. So, two questions come up. Is the economic pie growing well and is it getting distributed equitably among those who joined this monolith? This is where the opposition sees an opportunity to wrest back electoral ground by weaning back the sub-identities of caste or region from the monolith. While there are a lot of government claims about the pie growing, citing GDP and GST growth data, the real manifestation of these in terms of job creation and improvement in living standards isn’t apparent to a lot. There’s a sense that the K-shaped recovery that started after the pandemic has continued to run its course since. And in any case, there’s always a case anyone can make against inequitable growth in a $2200 per capita economy. This feeling among those who joined the BJP consolidation party that they have been taken advantage of for electoral gains can be easily fanned. That’s exactly what the leader of the opposition did with that halwa speech. He further compounded it with a demand for caste-based census. The focus of the budget on job creation and the subsequent speeches by the Finance Secretary about the rich paying more taxes are efforts to allay these concerns. The risk the BJP runs is these will prove insufficient to withstand the centrifugal forces at play to break the monolith. Rather, it will risk the wrath of the middle and upper class/caste votes that have traditionally been their core with such efforts. As you can see, the deck is stacked against the forces of consolidation. It will require some kind of genuine political masterstroke to continue with the consolidation. The conservative option for the BJP is to realise this difficulty and focus on rebuilding alliances with partners. But that ability remains to be tested. Left to itself, all the opposition needs to do is to do what it is doing. Let the limits of consolidation come into play and wean away one sub-identity at a time from the consolidated base. Politically, it is a no-brainer to do this. But there are consequences to this approach. Caste census can be a useful policy tool in the right hands. But this reductionist idea of delivering social justice through its arithmetic runs the risk of the Balkanisation of all political formations into smaller caste-based interests. Then, there is the risk on the economic front. Faced with the risk of disaggregation of their vote base, the current government could double down on redistribution to stem the tide. Redistribution, like we never tire of telling, should follow growth. Not come before it. Doing it without devoting undivided attention and resources to spur growth will be a travesty. But we are past masters at doing exactly this. The corollary to this is the opposition gets wedded to these ideas that are good politically to upstage this government but terrible if you actually follow through on them when in power. That should worry anyone who is looking forward to this sequel. Addendum—Pranay KotasthaneNow we know that the judgment’s reference to the application of the ‘creamy layer’ principle to SC/ST reservations lacks legal enforceability because it was not directly related to the questions of the case. Nevertheless, it does have political and policy consequences, and it might surely spawn a number of other cases that ask precisely this question. It is good that such questions are being asked. I find it odd when people argue that reservations should be retained regardless of income level because ‘increasing one’s wealth doesn’t address the problems of historical marginalisation’. In fact, such an argument is an admission of the fact that quotas are a grossly inappropriate tool. The whole premise of reserving economic opportunities for individuals from historically marginalised backgrounds is to compensate for past social injustices through economic and political means. Of course, that will never set right historical injustices by itself. If addressing historical injustices were the aim, the State could deploy other tools. Perhaps the law banning untouchability alone would suffice. Or maybe it needs to be supplemented with a South African-style truth and reconciliation commission. To argue that reservations for jobs cannot set right historical injustices but should nevertheless continue across generations is convoluted logic. You can’t argue for correcting past injustices through favourable economic opportunities while arguing that better economic opportunities can never address past injustices. Because if you do, quotas become a policy with an undefined output (measurable target) and an undefined outcome (the desired long-term social change). A discussion on alternatives to quotas should definitely be welcomed from a public policy perspective alone. No policy made seventy-five years ago can be defended on the grounds that improving it isn’t possible. In that spirit, I want to re-up an alternative that Nitin Pai and I had proposed a few years ago in FirstPost:

In essence, this solution tries to solve for both “merit” and “disadvantage”. The opponents of reservation claim that quotas directly undermine efficiency and merit. The proponents of quotas, on the other hand, find the notion of merit completely odious. In contrast to quotas, the composite score solution acknowledges that some assessment of “merit” is inescapable, even desirable. But it also doesn't ignore the problem that disadvantaged individuals face. Hence, we believe it is a better solution than quotas. We may well be wrong, but the Supreme Court judgment has signalled that it’s okay to think of better solutions. P.S.: How can we end this discussion without Pratap Bhanu Mehta’s hard-hitting take on the Leader of Opposition’s speech in the Lok Sabha? Here are a few points worth reading and reflecting from his Indian Express column:

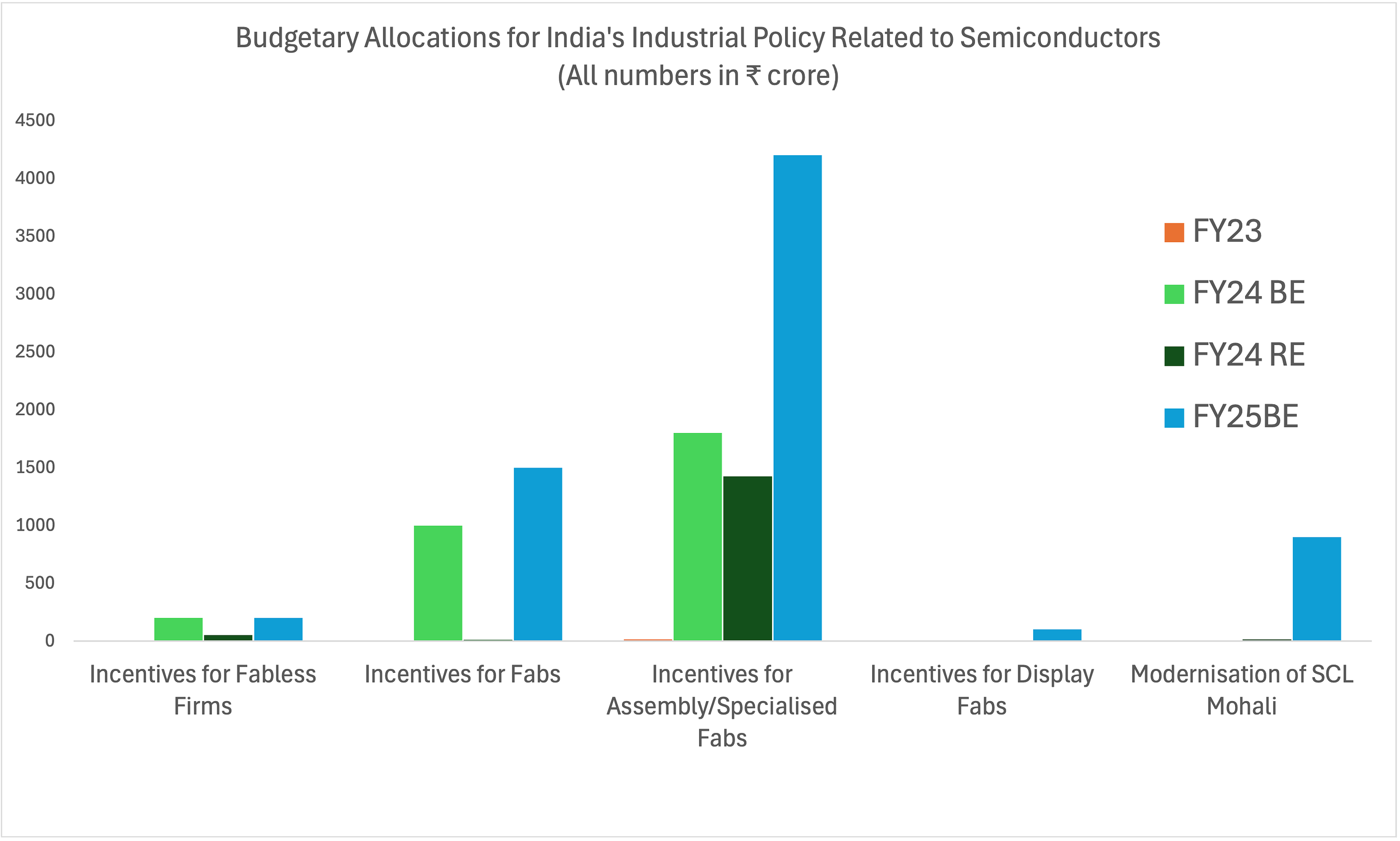

India Policy Watch #2: Promise vs RealityInsights on current policy issues in India— Pranay KotasthaneA defining characteristic of low state capacity is the difference between funding promises and funding deployment. In other words, ex-ante Industrial Policy promises can be orders of magnitude higher than the actual disbursement. This is a typical problem with the umpteen (fourteen, to be precise) Production-linked Incentive schemes. Out of the promised outlay of ₹1.97 lakh crore, the actual cumulative disbursement has only been around ₹9500 crore, i.e. 5 per cent of the total outlay. If the government were to continue at this run rate, it would take another twenty years for the promised outlay to be deployed. The reasons for this vast gap are twofold. In the first stage, ministries promise hefty PLI outlays to signal their relative importance—the more the outlay, the more prestige they get. These outlays span across multiple years. Given that budgetary allocations are done on an annual basis using cash accounting principles, the PLI outlay figure is a pie in the sky. Sometimes, these outlays don’t figure even in budget estimates because the line ministries can’t even get them off the ground. Secondly, even when budget estimates take PLI expenses into account, the actual disbursements often fall far short of them. This can be due to investment delays by firms, bureaucratic delays in approving PLI claims, or both. Nowhere is this difference between ex-ante Industrial Policy promise vs on-ground reality starker than in semiconductors. The government promised a $ 10 billion (₹76000 crores) incentive package in December 2021 with much fanfare. Crucially, the government frontloaded the disbursement on an equal footing basis during capital acquisition and construction stages instead of making its financial support incumbent on production. Given that two financial years have passed by since then, the FY25 budget provides the first snapshot of how the projects are proceeding in reality. And it doesn’t look pretty. The above chart contains all budgeted and disbursed amounts thus far. The government expects to disburse a total of ₹11419 crores, or 15 per cent of the promised outlay, by the end of this financial year. Breaking down this overall number indicates the health of each of the sub-schemes.

So, the lesson here is to take all claims—celebratory or critical—about industrial policy subsidies in India with a bucket of salt. The promises don’t translate to reality. These incentives aren’t going to be disastrous, as much of the recent commentary judging these fantastical outlays only on the basis of the jobs they create indicates. Neither are they putting India on the path to becoming a manufacturing superpower. These subsidies can, at best, be described as cute solutions pretending to address a much deeper problem. HomeWorkReading and listening recommendations on public policy matters

* From Kabir’s doha - जाति न पूछो साधु की, पूछ लीजिये ज्ञान, मोल करो तलवार का, पड़ा रहन दो म्यान। (Value a person’s qualities and not their caste, just as we value a sword and ignore the scabbard) If you liked this post from Anticipating The Unintended, please spread the word. :) Our top 5 editions thus far: |