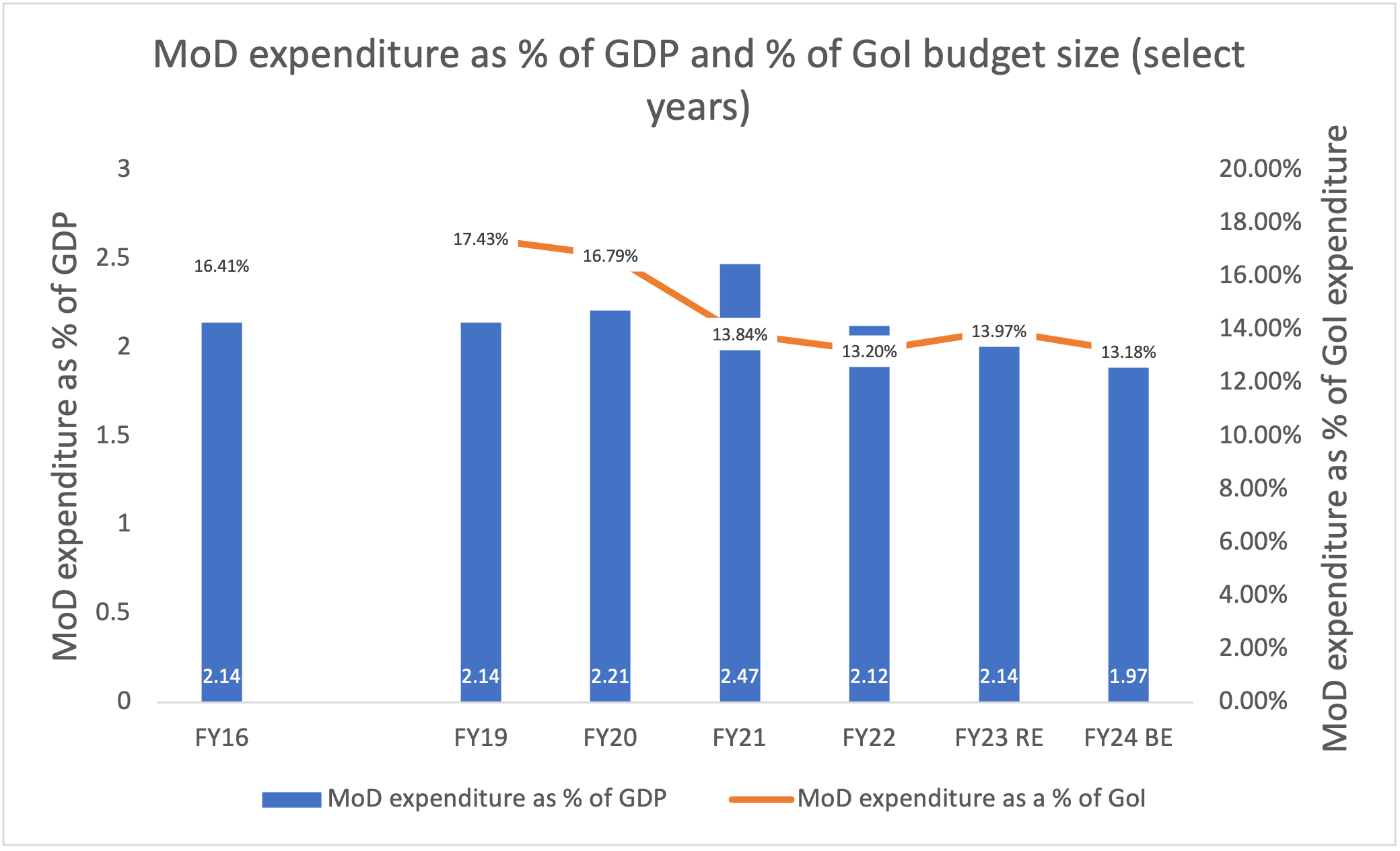

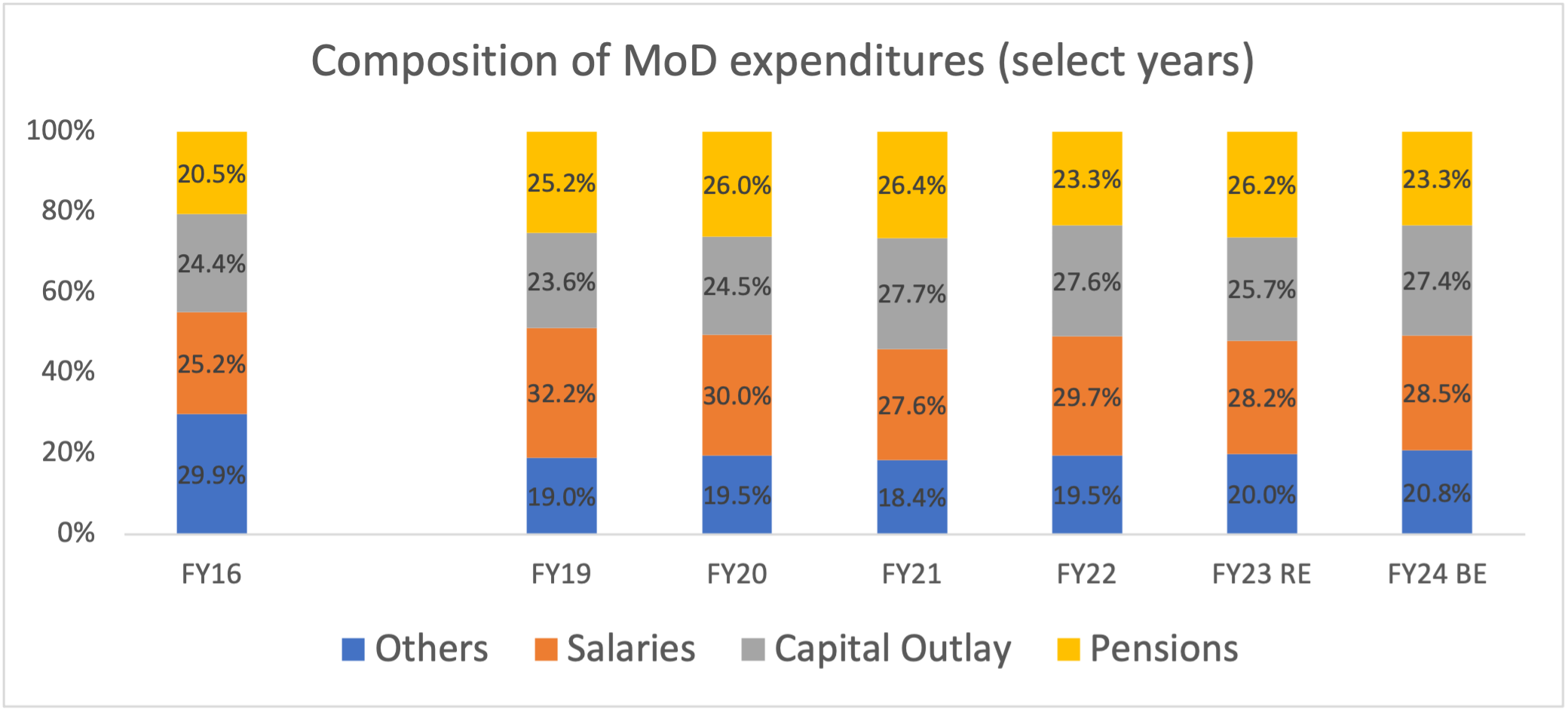

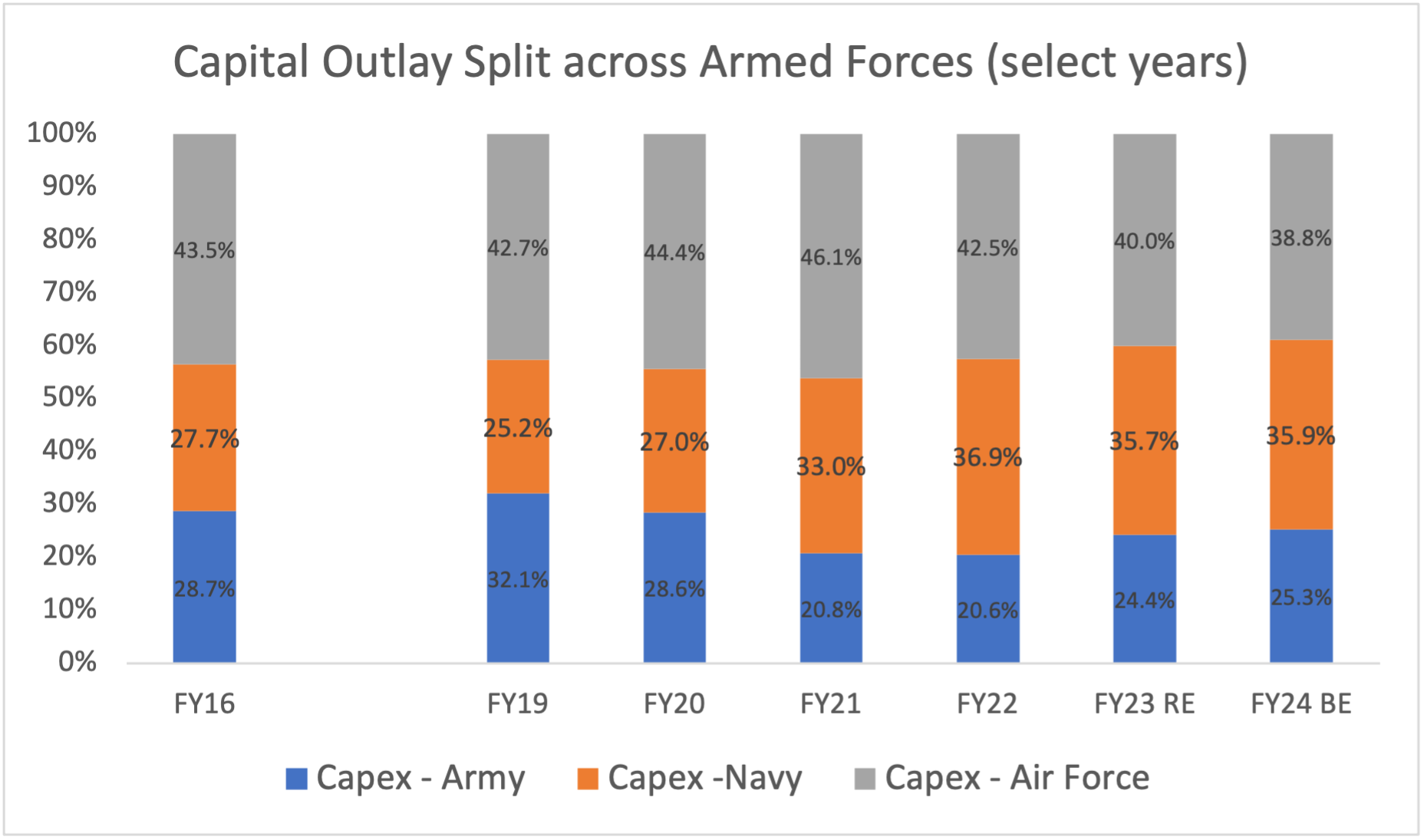

While excellent newsletters on specific themes within public policy already exist, this thought letter is about frameworks, mental models, and key ideas that will hopefully help you think about any public policy problem in imaginative ways. Audio narration by Ad-Auris. If this post was forwarded to you and you liked it, consider subscribing. It’s free. #201 Blocking out the SunThe Underlying Story of Defence Budgets, The Transparency Imperative, and How the Censor Board is at it Again.India Policy Watch #1: What Do Successive Defence Budgets Reveal?Insights on burning policy issues in India— Pranay Kotasthane(An edited version of this article was published in Hindustan Times on 13th Feb) Another defence budget zoomed past us on Feb 1. Since then, analyses have focused on how the defence spending for the coming year departs from the last year. Some have waved a red flag as defence spending has fallen below 2 per cent of GDP for the first time in many years. On the other hand, the defence ministry’s post-budget press release emphasised a 44 per cent increase in operational spending, which is expected to “close critical gaps in the combat capabilities and equip the Forces in terms of ammunition, sustenance of weapons & assets, military reserves etc.” The ministry also highlighted that the capital outlay for modernisation and infrastructure development has risen by a seemingly handsome 57 per cent over the last five years. How, then, do we make sense of these conflicting narratives? Comparing allocations with those in the previous year gives us a confusing picture. Every interest group can pull up a number from the budget to suit their pre-formed narrative. Taking a step back from these narratives, this article will show that this was another run-of-the-mill defence budget, just like the previous one was. Nothing in it indicates any significant change in the defence posture. Unlike Japan, which has announced a doubling of its military spending in the next five years, India’s approach is about gradually improving the operational efficiency of the armed forces. Looking under the hood This article looks at the defence expenditure over the last six budgets to make sense of the numbers. To put numbers into context, let’s use an earlier year (FY16). FY16 is a useful reference point as it predates two major developments: China’s visibly aggressive posture on the border and the budgetary commitments arising from the One Rank One Pension (OROP) scheme. Three observations follow from such an analysis. One, not only has defence spending fallen as a proportion of GDP, but it has also fallen as a percentage of government expenditure. In other words, defence has slipped in priority relative to non-defence functions (Figure 1). Two, the China challenge hasn’t led to any spectacular change in the composition of defence expenditure. Defence spending can be divided into four major components: salaries, pensions, capital outlay, and others. As Figure 2 shows, capital outlay was being squeezed by rising pension expenditure over the last few years. For two consecutive years (FY19 and FY20), more money was spent on pensions than on capital acquisition and modernisation. The balance has now been marginally restored since FY21, after the Galwan crisis flared up. Crucially, the rises in pension and capital expenditures have come at the cost of operational and maintenance expenditures, including ammunition stores (under the Others category). It is hence not surprising that the latest budget is trying to arrest this decline in combat capabilities. Three, this period has been relatively better for the Indian Navy in terms of capital expenditure. Since the procurement of new platforms happens over multiple years, a temporal view is useful in analysing how capital outlay is split between the three armed forces. Figure 3 suggests that the big change in the last four years is in the capital outlay for the Indian Navy, with the FY24 figure having doubled in absolute terms since FY20. The Big Picture By connecting these dots over the last five years, the picture that emerges is this: the government seems confident that China can be handled without a substantial rise in defence expenditure. The latest budget serves as a bellwether indicator for this claim. It was the first budget of the post-pandemic period, at a time when the economic prospects for India had improved considerably. The government achieved better-than-expected buoyancy in income taxes and GST in the current financial year, while the cooling of global fertilizer prices has led to a decline in the projected subsidy bill. Consequently, the government, for the first time in many years, had some fiscal room to play with. It has used that space to increase the overall capital outlay to Rs 10 lakh crore, almost three times the outlay in 2019-20. Despite this increase in the overall capital outlay, the defence budget resembles the middle overs of a one-day cricket match. From a financial savings perspective, there have been just two important changes over this period in the defence domain. The first was the announcement of the Agnipath scheme. It might reduce the pension burden, but these savings will reflect only after a decade-and-a-half. Other proposals, such as theatre commands, haven’t come to fruition yet. The proposal to create a non-lapsable fund for modernisation — a proposal the union government gave an in-principle agreement way back in Feb 2021, still hasn’t found a mention in the latest budget. Probably, the defence budget is the wrong place to infer India’s strategic posture against China. Perhaps, the government considers other tools of statecraft—diplomatic, economic, or non-conventional—more suitable for the purpose. This point needs deeper reflection. The discussions over the roles of these tools of statecraft currently operate under mistaken assumptions. Attempts at getting India into an anti-China alliance are spurned at the altar of “strategic autonomy”. The opponents seem to assume that India only needs to equip its armed forces with greater firepower. For too long, many parliamentary standing committees and defence organisations have gone hoarse trying to convince the government that defence expenditure should be raised to 3 per cent of GDP. If anything, the change is in the opposite direction. The defence budget trends are a reminder that the government does not prefer using the military instrument to outflank China. At best, it wants to equip the armed forces such that China’s incursions can be matched or repulsed. Given that there’s no significant increase in allocations for the Navy and the Air Force, it also means that the government is not considering an increased presence in the South China Sea. So, the military is being equipped to plug a vulnerability and not to gain an asymmetric political advantage over China. This line of thinking probably makes sense. There’s no point in matching China’s defence spending dollar-for-dollar. After all, the Indian armed forces are more adept at fighting at high altitudes. But this line of thinking should also make it apparent that India must develop capabilities in domains other than those involving force to inflict pain on China. The government should build a political consensus — closer relations with China’s adversaries are not a matter of choice but an imperative. That we need to double down on economic growth and technological upgrading if we are to constrain China’s hand in other domains. It also means that we shouldn’t be indiscriminately banning China’s investments in India; a better approach would be to make their companies in non-strategic domains more dependent on the Indian market. We will then have more tools in our kit to deploy if the situation on the border worsens. Each of these posture changes needs an updating of our priors and payoffs. For that to happen, it is necessary that the government comes clean about China’s incursions. Pretending that all’s well might give us false comfort, but it will also dissuade the strategic establishment from confronting the tough trade-offs in non-military domains. Without this pivot, we would merely rely on hope as a strategy. India Policy Watch #2: Through The Looking GlassInsights on burning policy issues in India— RSJWe talk about the arbitrary powers of the state on these pages often. Now, we cannot grudge the state's sovereignty because we have voluntarily handed it that power. One argument that follows from this is that such power is often prone to be used arbitrarily. And that’s a problem for the citizens. The typical solution we have offered on these pages over time is to restrict the domain of the state to a narrow set where it can make the maximum impact or to design its incentives in a way that makes the state act with accountability. Now, these are good design principles. We could use them to create structures and institutions that are strong and independent that could hold their own against any arbitrary use of power. But are these enough? A natural question that should follow is how do we know things are working in practice like they were meant to? How do we get authentic information about how the state is conducting itself? How do we confirm that it is not subverting the institutional design that is in place to control its powers? These questions lead us to the other pillar of a well-functioning democracy - transparency. It is a topic we haven’t discussed enough on these pages. Transparency is a moral good, and it is vital for a healthy democracy. Darkness stunts democracy. It needs light to thrive. In the early part of the 20th century, the US Supreme Court judge Louis Brandeis famously remarked, “sunlight is the best disinfectant” while making a case for a transparency imperative. Or, if we were to go further back, Bentham, often credited to have done the most original thinking on transparency, summed it up with - the more strictly we are watched, the better we behave - a principle he put at the heart of his advocacy for an open government. So, what has triggered my early morning ruminations on transparency? Well, there are two reasons. Here’s one. The Indian Express reports:

Bravo. The Chief Justice was almost channelling Bentham there, who famously wrote, “secrecy, being an instrument of conspiracy, ought never to be the system of a regular government.” I mean, what even is a sealed cover in a matter that concerns millions of ordinary investors? Why should there be secrecy in the name of experts and their recommendations? A sealed cover is a strange invention. It gives the sheen of a fair and independent process to what is essentially a subversion of a democratic principle. It ranks up there among one of the great Indian coinages. The top spot, of course, is forever occupied by ‘mild lathicharge’. And now, onto the other reason for all this talk on transparency. This was the headline-grabbing news of this week in India - “Weeks after its documentary taken off, BBC gets I-T knock”. Here’s the Indian Express reporting on this with many quotes from “unnamed government sources”:

A very garrulous source there with a lot of information. I don’t want to ascribe motives to the tax raids yet. There’s enough in the timing of these ‘surveys’ to raise suspicions. The I-T department has been used to settle political and other scores for decades. It speaks poorly of our institutional strength and independence. But that’s not the issue we are discussing today. The question is about transparency. Does anyone know why the surveys were carried out? The sources have cleverly given some reasons, but what stops the department from giving an official reason for them? Is it because it is likely that if they give the official reason, there will be further questions on the arbitrary nature of the actions? So, it is best to share nothing officially, selectively leak information to the media to paint the BBC in poor light and get away with harassment that then sends a message across to other foreign media outlets. Because even based on the merits of what the sources have said, it is difficult to justify a two-day survey. To quote the same news report:

It shouldn’t surprise anyone that political actors don’t like transparency. It adds to their burden of accountability and increases the political costs of any missteps, deliberate or otherwise. So, how should the citizens keep up the demand for transparency in a democratic setup? After all, for the citizens to be involved in the governance process, they must have access to the government's information, plans and intentions. Also, there is a line beyond which too much transparency could be counterproductive. Too much information, too early in the process, could mean stalling the plan as interest groups jump in and skew the decision-making process. I have outlined three frames that one could use to think about transparency in a democracy. First, it is in the long-term interest of political parties to seek transparency in a democratic setup. For those in the opposition, it is about making the incumbent party in power more accountable. For the incumbent, too, there’s always the uncertainty about the future when they might not be in power. In such a scenario, it is better for them to have stronger laws on transparency for their own access to government information, which they can use to hold others accountable. A lack of certainty about future electoral prospects for any party is a feature of a good democracy. It is in this environment most transparency laws are made. In India, too, the RTI came about because of grassroots activism and a broad consensus among the political class led by the party in power then. However, it is important to note that the Overton window was right during that time when getting re-elected was an exception. It meant the political actors were keen to have access to information in future. In that sense, any period when transparency is suppressed in a democracy is a good surrogate for the power of the party in power. In India, the RTI laws allow for access to a significant amount of government information. The problem is that there is a gradual erosion of its ambit as the dominant political class comes to view it as an irritant. The only way to counter this is for the citizenry to continue using the RTI tool to its fullest extent. The more people know the tool's power, the harder it will be to blunt it. Second, it is important to devolve transparency to state and local governments. This is where the political uncertainty is still high in India, which means there’s an incentive for political actors to support transparency moves to guarantee their own access to information in future. This is also the space where petty corruption is still rampant. One of the challenges of RTI in India is that most of the activism here is focused on big-ticket issues. The opportunity to bring sunlight as a disinfectant and its payoffs are the highest at the local level of governance. Separately, there are also specific areas in the private sector that could do with improved transparency. This is tricky territory, and let me be very specific about this. There’s a significant amount of information that’s collected, often without explicit consent, from the citizens by the private sector, which is then monetised in various ways. The mechanism by which their information is used and the extent to which the private sector, especially the social media platforms, benefits from it are not transparent to the citizens who are the customers. If your attention is being monetised through multiple trackers and personalised ads, it is only fair you must know the rules of the game and agree to play it. This is still a white space of policymaking in India. Lastly, the oft-cited risk of policy waters being muddied because of transparency, where various interest groups will lobby for their positions and slow down the decision-making process, is a bit misplaced. Those in favour of transparency do not argue for the innards of policymaking being put out for display. That process requires stakeholder mapping and seeking inputs in a way that’s been documented by various policy thinkers. We have written about the eight-step process of policymaking on these pages on multiple occasions. The issue of transparency is important in two areas. First, the implementation and measurement of a policy proposal. How did a policy fare compared to its promise? Were the public resources and efforts prudently used? Was there a clear understanding of why something failed? Access to this information is important for the public and experts outside the government to hold the government accountable and improve future decisions. Second, the size of the state in India often means it is the biggest, often the sole, customer in multiple sectors and its decision on setting the rules of games in these sectors, awarding contracts and its performance in managing its budget should be available for public scrutiny. Again, this doesn’t mean the government should vet its decisions at each stage with prevailing public opinion. Rather it must be able to explain its process and the rationale for decisions openly and transparently. The practice of sealed covers or I-T surveys and raids without a clear reason isn’t new to India. What’s new is the somewhat strange support for these actions by the mainstream media that are being fed by the ever-bizarre theories cooked by the partisans on social media. BBC isn’t doing a documentary on Gujarat because China is now funding it. Nor is there a leftist cabal that’s busy bringing Adani down one week and using BBC the next to show the government in a bad light. This playbook is reminiscent of the Indira era of the mid-70s, where in the name of national interest, we buried transparency and accountability. It took us decades to get out of that mire. Learning from history is free, but most of us fail the eventual test. PolicyWTF: Casually Banning Films Committee, RepriseThis section looks at egregious public policies. Policies that make you go: WTF, Did that really happen?— Pranay KotasthaneLast week, I came across an excellent report by Aroon Deep in The Hindu that explains how the Central Board for Film Certification (CBFC) is going way beyond its usual stance of “demanding” cuts of scenes showing sexual content, violence, or abusive language. Instead, the CBFC now also has a perspective on dietary preferences (demanding that mention of “beef” be struck off), foreign policy (demanding that references to ex-KGB officers, China, and Pakistan be removed), and even corruption (how can a filmmaker dare depict a police officer accepting a bribe?). Seriously, what an omniscient body. Despite its activism, the Censor Board hasn’t impressed the extremists. One Hindu group leader has called for creating a ‘Dharma Censor Board’ “to review Bollywood films and keep a check on any anti-religious content or distortion of facts about Sanatan Dharma.” In his words:

While it sounds absolutely absurd at face value, there is a liberal way out to assimilate this conservative critique. We covered it in edition #122, and I want to re-emphasise those points. In 2016, my former colleagues Madhav, Adhip, Shikha, Siddarth, Devika and Guru wrote an interesting paper in which they recommended that film certification should be privatised. Deploying the Banishing Bureaucracy framework, they wrote:

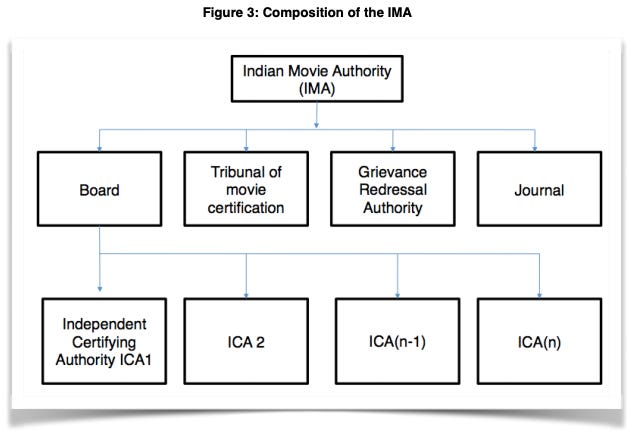

So, the Hindu group can very well have its own ICA, which will rate the movie on its Sanatana Dharma compliance score. But…

In other words, this solution reimagines the CBFC as a body that grants licenses to independent and private certification organisations called ICAs. These ICAs must adhere to certain threshold criteria set by the CBFC. Beyond these criteria, some ICAs may specialise themselves as being the sanskaari ones trigger-happy to award an “A” certification, while others may adopt a more liberal approach. In the authors’ words:

This solution has the added benefit of levelling the playing field between OTT content and films. Currently, the CBFC has no capacity to certify the content being churned out on tens of streaming services. By delegating this function to private ICAs, the government can ensure adherence to certification norms. In essence, just as governments can often plug market failures, markets too can sometimes plug government failures. Reforming our ‘Censor Board’ requires giving markets a chance. There’s much more detail in the paper about grievance redressal, certification guidelines, and appeals procedure. Read it here. HomeWorkReading and listening recommendations on public policy matters

If you liked this post from Anticipating The Unintended, please spread the word. :) Our top 5 editions thus far: |