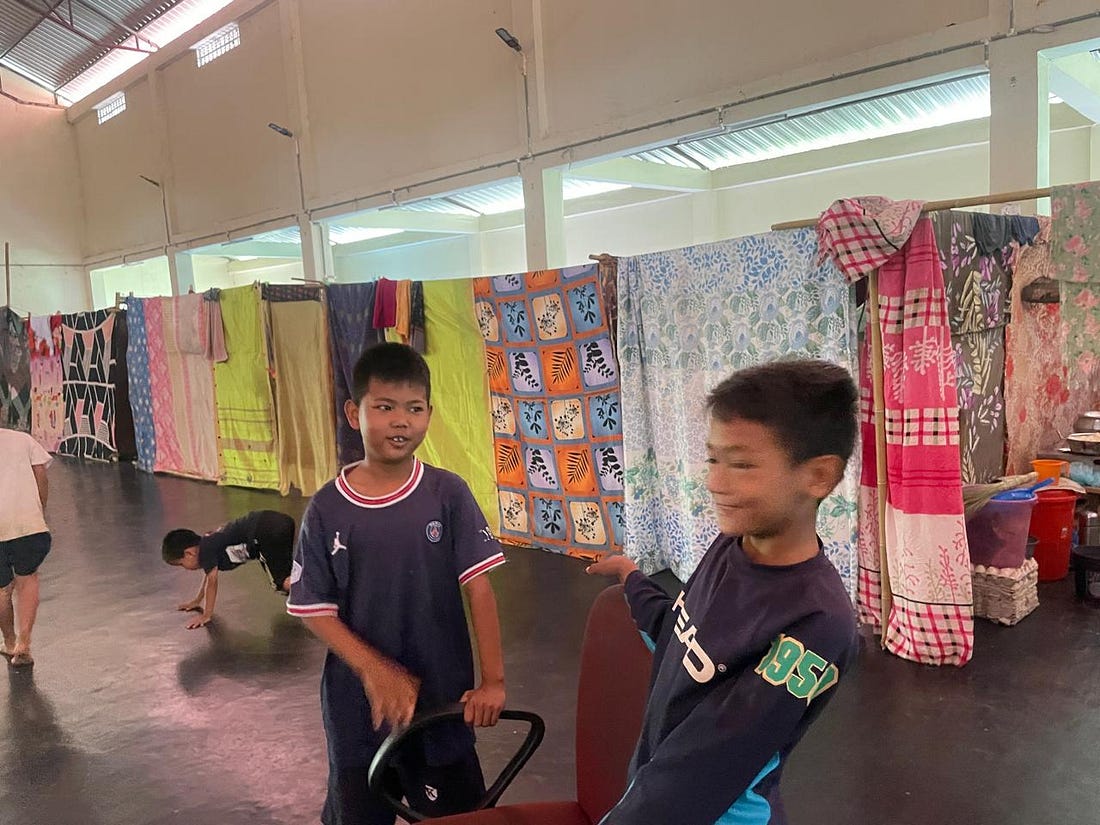

Sign up to have posts delivered directly in your email inbox. Much of the content will be free, and there will also be weekly posts for paying subscribers only. I will be reporting from India and the neighbouring countries on stories the world needs to hear. I will interview journalists, writers and public intellectuals known globally for their profound expressions of discontent. There will also be ongoing discussions and debates with experts, policy makers, leaders and creative professionals, on current affairs, crises and humanitarian concerns. They Were Just Colleagues in the Sky: Two Lives, One Divided HomelandFrom the cabin crew on the flight AI171 to the relief camps: Inside Manipur’s ethnic conflict, state surveillance, and a democracy’s failure to reckon with its own citizensOn the morning of June 12, 2025, Nganthoi Sharma Kongbrailatpam, a 21-year-old cabin crew member from Manipur’s Thoubal district, placed what would be her final call to her sister. “I’m flying to London today,” she said, her voice calm but excited. She reminded her that she wouldn’t be reachable until June 15—standard for long-haul international crew duty. It was a routine moment for a young woman living her dream, thousands of miles away from the tensions brewing back home. Hours later, her name would appear on national news broadcasts, one of the many lives lost in the catastrophic crash of Air India Flight AI-171 near Ahmedabad. Among the crew listed was another young woman from Manipur—Lamnunthem Singson, a member of the Kuki community. Like Nganthoi, she had chosen a career that demanded poise, professionalism, and quiet courage. The two women may have boarded that flight as colleagues, perhaps even as friends. But in their home state of Manipur, their communities—Kuki and Meitei—remain deeply divided by a conflict that has claimed lives, displaced thousands, and fractured the fragile social fabric of a land already long ignored by mainland India. If a kuki is seen in a Meitei village or a Meitei is seen in a Kuki village, their fate would most probably be cruel. This is taking place in the significant north eastern region of the world's largest democracy. In cities like Mumbai, where they were based, these women were not Kuki or Meitei—they were simply Manipuri, part of a broader Northeast Indian diaspora working in India’s booming hospitality and aviation industries. They likely lived in shared flats, helped each other navigate language barriers, and made late-night phone calls to their families back home. In death, their bodies returned to a homeland split down ethnic lines—lines that did not matter in the sky, but that determine everything on the ground. Nganthoi’s body was flown to Imphal, the state capital. But Lamnunthem’s body could not follow the same path. Because Kuki people are no longer safe in Imphal,the capital city. her remains were flown to Dimapur in the neighbouring state of Nagaland, then brought by road to her parents’ home in Kangpokpi district—a route carved not by logistics, but by violence and fear. “For those of us who have lost so much and still feel unsafe, why would we even consider going through Imphal?” asked her cousin, Ngamlienlal Kipgen. “This route may be our new normal, but it was anything but normal this time. People came together to honour my sister, bringing us so much comfort.” (https://www.outlookindia.com/national/the-road-not-taken-lamnunthem-singsons-final-journey-and-the-ruptured-cartographies-of-manipur) When I spoke to Kipgen about the decision to take his cousin’s mortal remains via the neighbouring state, he said : Since 2023, our new normal to travel back home has been through Dimapur (Nagaland) airport. We as a family decided to take her mortal remains through Dimapur airport because we felt it would be the most accessible for everyone who wanted to be there to receive her. Despite reassurances from the state, how could we even think of going back through Imphal, a place where we lost so much. However I want to stress the amound of love we received at Dimapur airport where hundreds of people lined to receive her” Speaking about his cousin who was a pillar of support for the family as they were displaced through the conflict, Kipgen tells me “The displacement of our family was a challenging time for us as a family during the conflict but Nunthem stepped up to be a pillar of support for her family, all she had to offer was love…” In death, Lamnunthem’s journey home became more than a return—it became a commentary on the cartography of grief in a state where every movement is political, every route a negotiation with danger, memory, and distrust. The two crew members of the Air India flight crash that killed 241 souls reminded the country of a brutal reality of a conflict that the democracy had tried to erase from its public memory. I travelled to Imphal, the capital of the embattled state of Manipur late last year. Nestled in India’s remote northeast, Manipur has been engulfed in deadly ethnic violence since May 2023, pitting the dominant Meitei community against the tribal Kuki-Zo groups. What began as a protest over land and political rights has spiraled into a brutal conflict displacing over 70,000 people. This border state—long overlooked by New Delhi—shares a volatile boundary with Myanmar, where a military dictatorship, civil war, and refugee flows have deepened unrest in the region. Ethnic ties blur the border, with Kuki-Zo communities living on both sides. The result: local conflict, fed by regional instability. Images from the reporting trip As Indian authorities struggle to contain the crisis, the violence in Manipur reveals deeper fractures—of identity, governance, and a state’s marginalization. What happens in Manipur carries implications far beyond its hills. It challenges India’s internal stability and its approach to policing a porous, insurgency-prone frontier. At the Imphal airport, the capital of the state of Manipur, an officer from the State intelligence walked up to me claiming to be an 'immigration officer'. I reminded him that Manipur was a part of India and I was an Indian national. He told me that he was aware of my previous reporting’s and wanted to know the context of my visit to Manipur. Later that day intelligence officials followed me to my airbnb in the state of Manipur, a case of serious state interference in reporting as documented by the Comittee to Protect Journalists (https://cpj.org/2024/11/indian-journalist-rana-ayyub-tailed-by-officials-harassed-after-number-leaked/0 But this story is not about me, it is the story of the state of Manipur, the concern over the surveillance of journalists and the obfuscation of truth. What was it that the Indian state did not want to be reported and how could a journalist report in the state and meet their sources without the fear of the sources being exposed due to surveillance. Over the past year, I’ve met dozens of young men and women from Manipur—both Kuki and Meitei—working in salons, spas, hotels, and reception desks across Indian cities. Far from home, they co-exist in shared apartments and tight-knit workspaces, performing with quiet professionalism in industries that value their grace, diligence, and adaptability. Employers praise them not for their ethnic identities, but for their work ethic and their willingness to learn. At a salon I frequent in Bandra, two women—one Kuki, one Meitei—sit side by side at the reception. They ask not to be named, fearful that even here, miles from Manipur, their shared presence could be seen as betrayal. Like the Air India hostesses, they’ve built lives in the sky and in glass storefronts—spaces where identity is suspended, at least temporarily. But they live with the cruel awareness that when they return home, the same names that mean little here will once again divide them, perhaps fatally. Mary, a 25-year-old masseuse from the Kuki-Zo community, has worked across India since she was a teenager. “To my employers, I’m just ‘North-Eastern,’” she tells me with a resigned smile. “They don’t know the difference between Manipur, Mizoram, or Nagaland—so how can they begin to understand the strife tearing through our homeland?” Despite years of experience, she says she often feels like a foreigner in her own country, frequently mocked for her accent or facial features. Outside the spa where she works, a sign reads: Best massage by North Eastern experts—a label that flattens distinct histories and cultures into a marketable cliché. Behind the quiet professionalism expected of her lies a daily performance: to be seen, but not understood. When I ask Mary if she plans to return home, she shakes her head. Her family, still in Churchandpur, has urged her to stay away and “secure her future.” She now shares a cramped two-bedroom apartment in Mumbai with eight other women from Manipur. Each of them earns roughly $400 a month, working 12-hour shifts, six days a week. “This is better than living in fear,” she says. Her younger brother had been studying at a college in Imphal, but once the violence began, he was forced to flee—walking, hiding, hitching rides—to Churchandpur, three hours away. “They would have chopped him to pieces had he not escaped in time,” she tells me. Now, cut off from his education and any real prospects, he spends his days watching Bollywood films on YouTube—a life paused, with no livelihood and no way forward. Despite the scale and duration of the violence, Prime Minister Modi who has claimed to be a vishwa-guru (somebody solving global crisis) has visited Manipur since the conflict erupted in May 2023. This silence has deepened the sense of abandonment among many Meiteis, who accuse the central government of looking away while their state burns. Meanwhile, members of the Kuki-Zo community say they have been left to the mercy of vigilante groups like the Arambai Tengol, believed to operate with the tacit support of the state government. The Chief Minister, N. Biren Singh—a Meitei himself—remains in power, despite calls for his resignation by tribal groups and opposition leaders. Ironically, while the Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA)—a controversial law that grants sweeping powers to the military—is still in effect across Manipur, rebel outfits continue to operate with impunity, assembling drones, crude bombs, and sophisticated weapons. The unchecked proliferation of such groups has raised urgent questions about state complicity, selective enforcement, and the real purpose of military presence in a region that appears to have slipped beyond the reach of both law and accountability. Around 60,000 people displaced from their homes in the hill and valley districts of Manipur have been living in relief camps since May 2023. In Kangpopki, another Kuki zo area, armed women check our belonging and ascertain our identity to see if we are Meiteis, they frisk our driver, a Muslim guy who happens to be from a neutral tribe. Long posters and hoardings with images of dead children asking for justice make way as stray dogs run behind our vehicles. Spray paint is used to write -Kukiland all over the walls. When I ask the Kuki leaders if they are looking to secede from India, they tell me about their patriotism but ask me if India loves them back, says Ng. Lun Kipgen, the spokesperson for the committee on Tribal Unity. He points out to the pictures of the dead children and says " The government of India is subservient to the government of Manipur and that speaks volumes". In a relief camp where women are making gruel to feed their children, a young boy, Zhem tells me that he aspires to play like Messi. His father died in the relief camp due to a genetic heart condition and he needs immediate help. His is not the only heartbreaking story. Countless members in the camp talk about escaping armed militias including a pregnant woman who gave birth in the jungle while fleeing the conflict and is now in a relief camp in Kangpopki. As we enter the Kuki heartland, another banner catches my eye " Why not Kukiland-Separate administration- Save the Indian citizens from the brink of Talibanisation !! As we cross Churchanpur border, the paramilitary forces grill us about the people we speak to, the names and addresses of people we meet. Every few miles is a check post, one officer tells me that he knows that there are cases against me Just across the Churchandpur border lies the Torbhung Gram Panchayat where the women or the armed militias or soldiers of the rival Meitei tribe sit in a circle as they ask me to record their story "Please go and ask the Indian government why is the democracy not reaching us-Why does the Prime Minister of India who is travelling to global summits unable to stop the killings of our families, our children, why are we being orphaned, why are the militants targeting us". The women show me the burnt houses that they claim were burnt by Kuki insurgents. The grief is real, the angst is real, in the world's largest democracy where thriving G20 summits and other world leaders are hosted, a civil war is taking place the last two years. During the height of the Manipur conflict, authorities imposed a prolonged internet shutdown, ostensibly to curb the spread of misinformation and maintain public order. This digital blackout lasted for months, effectively silencing voices from the ground and cutting off communities from each other and the rest of the country. When the internet was partially restored, the release of a horrifying video showing the sexual assault of a Kuki woman by a mob of men sent shockwaves across India. The video, which had been filmed weeks earlier, became a grim symbol of the unchecked ethnic violence and the deep failure of law enforcement during the unrest. In cities like Mumbai, Manipur’s sons and daughters live side by side, stitched together not by politics or history but by necessity and longing. They speak of home with both pride and fear, aware that return is no longer simple, or even safe. India’s metropolises have given them anonymity, income, and space to dream—but not immunity from the forces that split their homeland. The crash of Flight AI-171 may have made headlines, but what it revealed was a quieter tragedy—of a people suspended between flight and return, recognition and erasure, survival and sorrow You're currently a free subscriber to Rana Ayyub's Newsletter. For the full experience, upgrade your subscription. |